Additional

Rule – Rule 5

In the

walked parts of each section, whenever a station on another line is nearby it

is permissible to include them on the same trip.

Now,

there are 4 District Line stations between Acton Town and Hammersmith. I can

distinctly remember the Piccadilly Line stopping at all of them, however that’s

not the case now. So as not to cut off my nose to spite my face, I decided to

do all of these stations as part of this section. What’s more, it seemed like a

good idea to use this as my walked section.

So, a brisk

walk from Acton Town to the North Circular, and then back to the junction with

Chiswick High Road. Incidentally, this took me past Gunnersbury station.

Gunnersbury is on the District line branch out to Richmond. The area is known

as Gunnersbury since King Canute gave it to his daughter Gunnhild in the 1000s,

hence it became known as Gunnhilds Burg, or Gunnhild’s Mansion. Frankly, I had

no wish to linger around the station once I’d taken my requisite photographs. The

entrance is through this undistinguished portal into a rather nasty 1960s

block. Nothing remains to suggest that the station was actually damaged in the

London tornado of 1954. Still, if nothing else, at least Gunnersbury was the 27th

active station of my challenge. What’s the significance of that, you might ask?

Well, bear I mind that there are currently 270 stations, this meant that I’d

actually visited 10% of them already. I tried to push the thought that there

were still 90% of them to go out of my mind.

Chiswick

Park, on the other hand, has much to appeal to the eye. Research suggests

that Charles Holden’s design was inspired by Krumme Lanke U Bahn station

in Berlin. Well, I never visited that

station when I was there. Photographs suggest a resemblance in the sense that

they’re both modernist designs, with semi-circular features, but not much more

similar than that. Chiswick Park has the brick, glass and concrete so typical

of Holden’s other designs. I definitely remember Piccadilly Line trains

stopping at Chiswick Park when I was a kid, but I believe that they never stop

there now, and that this is the only station on the Ealing Broadway arm of the

District Line that is exclusively for the District Line.

Mind you, for most of the day Piccadilly

Line trains don’t stop at Turnham Green

either, only early and late. Turnham Green is one of very few Underground

stations to share its name with a battle. In this case, the Battle of Turnham

Green was the opening battle of the English Civil War. Despite such historical

connections, though, Turnham Green Station really isn’t worth getting off the

train for. Luckily, this was my walked section, and it took slightly less than

15 minutes along Acton Lane and Hardwick Road. I was unable to discover when it

was built, but the whole thing is like a large shed tacked onto the side of the

viaduct which carries this raised section of track between Acton Town and

Hammersmith. It’s a little reminiscent of the old building at South Ealing. If

you look at the sketch I’m sure you’ll appreciate why I didn’t want to linger

here either.

10 minutes

walk and I arrived at Stamford Brook

station. This one dates back to 1912, and I have to say that I rather like it. The

only notable thing that I found out about it is that in the year I was born it

had the first automatic ticket barrier in the network installed. The station is

about the same sized as a cosy suburban house, but the semi circular gable gives

it an air of importance, as does the ornamentation on the brickwork. I

considered getting back on the train here, but decided to push on.

Again, it only takes

about 10 minutes to walk between the two stations, and the last five minutes of

this were through a very pleasant little park – possibly the park from which Ravenscourt Park station takes its

name. I was actually rather surprised by the size of the station’s ticket hall

when I approached it. This is another of those stations I’ve passed through

many times, but never actually walked into or out of. I haven’t been able to

find out when it was built, but I’d imagine that it’s earlier rather than

later. It may even be the original building from 1873.

Having

bagged 4 – or if you count Gunnersbury, 5 stations, I decided that the best

thing I could do was get the District line to Hammersmith, short journey

though it is. I’ll be honest, I didn’t want to arrive at Hammersmith on foot,

because there is no station building now, as such. The station is

entered through a 1990s shopping mall. Which I swiftly left, because I wanted

to go to Hammersmith station. Let me explain that. There are actually two

Hammersmith stations, the District and Piccadilly Line station, and the

Hammersmith and City line station. This latter station is well worth a short

walk to visit, even though I wouldn’t actually be doing the Hammersmith and

City Line for quite some time. For one thing it was the oldest station building

I’d yet sketched, dating back to 1868. I have family roots going back to my 3x

great grandparents in Hammersmith, and it’s pleasing to me to think that they

would have been familiar with this very building. Amazingly, though, this

wasn’t the first Hammersmith station, since the original was built a short way

north, in 1864.

Now, let’s

talk about Baron’s Court. I have passed through the station many times,

but never ever alighted there. In fact to me, Baron’s Court was just a name,

and a set of distinctive red benches. So you might imagine how surprised I was

to walk out of the station, and find this frankly beautiful station building. It

slightly predates Leslie Green’s stations, although I venture to say that you

can see some of the features that Green himself would adopt and adapt. This

station was designed by Harry Ford, who was the chief architect of the District

Railway from 1900 until 1911, so his career overlapped somewhat with Leslie

Green’s career as chief architect of the Underground Railways Company of London.

Another

district line detour next, I’m afraid. The Piccadilly Line goes direct from Barons

Court to Earl’s Court, but it does this through nipping underground on the

approach to Earl’s Court, while the District Line manages to squeeze in another

stop at West Kensington. I don’t honestly think that West Kensington is the

kind of station you’re ever likely to be drawn to for its aesthetic qualities, and

the only reason for me to take the detour was that it was a very convenient way

of lightening my District load a little when the time came. Apparently it is a

Charles Holden design, but I have to say that it’s one of his least effective.

Well, that’s Holden. Going back to Harry

Ford and Leslie Green, if you want to see an overlap of their two styles you

just need to go to the next station on the line, Earl’s Court, since

this was a collaboration between the two men. Well, the façade was, anyway. The

main part of the station is John Wolfe Barry’s from the 1860s. As for the

façade, well it has the familiar semi circular windows of Leslie Green’s

stations, but the terracotta tiles are much lighter in tone than his trademark

ox blood tiles, and in fact the tiles of both Earls Court and Barons Court are

far more similar in tone to those on the front of the Natural History Museum. Research

suggested that it would be worth walking through the station to take a look at

the other entrance on Warwick Road. This was built in 1937, and space was added

for offices on the roofs in the 60s. Which is a bit of a shame, since the

coloured glass screening obscures a lot of the original 1930s features, which I

find more pleasing on the eye.I did

consider making another District Line detour at this point, to Olympia. However,

from my ays of visiting a friend who lived within sight of Olympia, I recalled

that it’s only a short walk from High Street Kensington, and so it made more

sense for me to leave it until the District Line as part of a walked section.

I don’t know for certain that the

District Line station building for Gloucester Road station is the

original, but I’m pretty sure. The moulding below the ornate cornice and

balustrade on the roof of the building declares that this is the Metropolitan &

District Railway. It’s a pretty, Italianate construction, with a rather lovely

glass canopy above the entrance. The two small wings on either side give the

whole building a pleasantly symmetrical, pretty much palladian appearance. This

is enough beauty for any station, and yet there is also the Leslie Green

station building as well, built for the opening of the GNPBR. It’s the first

station on this challenge to feature the famous ox-blood terracotta tiling, but

to my mind it looks slightly unbalanced and less harmonious than the typical

Leslie Green stations, since the first storey abruptly ends before the ground

floor does.

One other feature of the station is that

the disused Circle line platform houses an Art on the Underground exhibition. Since

we’ve been speaking of exhibitions, it’s ironic that the next stop is South

Kensington, since it’s famous as the tube station for the Science Museum,

the Natural History Museum, and the V and A, which it can be claimed all had

their genesis in the Great Exhibition of 1851. I remember back in the early 80s

being surprised to discover that there is actually a street level station

building, since every time I’d used the station prior to this I’d taken the

pedestrian subway to the museums, and these just emerge from glorified holes in

walls. As for the station building, which is a few streets away from Exhbition

Road and the Museums, well, the first thing you notice is the façade of the

original turn of the century GNPBR Leslie Green station. However the actual

entrance to the station is through the Metropolitan and District entrance. I have

to say that the elegant columns really aren’t well served by the blocky generic

blue canopy bearing the stations name, which just serves to distract from the

delightful ornamental metal work between the columns with the station name and

the Metroplitan and District Railway. It’s a bit like a gentleman in his 80s

sporting an electric blue Mohican.

At this point in the trip I parted

company with the District and Circle Lines, and continued with the Piccadilly

to Knightsbridge, probably best known as being the station you get off

at for Harrods. The original 1906 Leslie Green main entrance went the way of

all flesh in the 1930s, although the former rear entrance in Basil Street, with

its ox blood tiles and all, still exists as part of an office building. In the

1930s the station was remodelled to install escalators to the platforms, and it

was necessary to demolish the ticket hall, and built the one which stands there

now into the corner of an existing building. So either you take the building as

a whole and say that it’s one of the most impressive station buildings, or

you’re honest and say that the station building is just a small part of this

and it’s really not that much to write home about

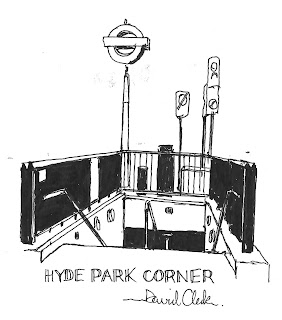

Which still makes it more

impressive than our next stop, Hyde Park Corner. This is our first hole

in the ground type station, and as you can probably see from the sketch there

is little attempt at sweetening the pill, or humanising the dirty concrete with

any sort of canopy, a la the Paris Metro. The sad thing is that the original

station building, a Leslie Green 1906 effort still stands on the south side of

the road junction. As with Knightsbridge, the building proved an obstacle to

the installation of escalators in the 1930s renovation, and was closed and

replaced with a completely underground ticket hall. That about wraps it up for

Hyde Park Corner, and I have to admit that even though I’d already ticked off

my between station walk, with the sun shining I decided that a walk along

Piccadilly to Green Park might be pleasant.

Indeed it

was, too. I will admit to a brief detour along Down Street to see one of the more

famous of the London Underground’s ‘ghost stations’. Down Street was

originally a stop between Green Park and Hyde Park Corner, which opened in

1907, and closed, due to lack of use, in 1932. The Leslie Green station

building still remains, but probably wouldn’t be much remembered other than for

the fact that it was used by Winston Churchill as a bunker during World War II.

Apparently it is possible to access the underground levels of the station, and

occasionally London Transport has allowed the privileged few to do just that.

Well, I’m not one of them so after pausing to buy a paper from the shop which

occupies part of the building, I pressed on to Green Park.

Green

Park is another of those Piccadilly Line stations which acquired a

subterranean ticket hall in the 1930s, although the entrances are at least a

bit better than Hyde Park Corner’s. The main entrance is accessed through a

building which houses, amongst others, retail outlets including Marks and

Spencers. It also has its own hole in the ground entrances. The hole in the

ground entrance on Piccadilly has a rather

uninspiring concrete shelter

above it, while there’s another 21st century entrance through

Green Park itself, and I have to say that for all its simplicity, I rather like

this entrance.

I was

already well aware that the large booking hall of Piccadilly Circus

station was underground. The original Leslie Green station building closed in

1929, yet it continued to stand until being demolished in the 1980s. Shame,

especially since it means there are no surface buildings associated with the

station now. At least each of the 4 entrances has a rather imposing gate way

consisting of ornamental lamps and metalwork with the Underground sign over

head between them.

The Piccadilly Line stations come thick

and fast above ground on this section of the line, and I knew for a fact that I

could walk from Piccadilly past Leicester Square to Covent Garden a lot more

quickly than I could take the tube between stations, get out at each and then

get back on the train again. So continuing the above ground walk was a no

brainer. Besides, this is a part of London I used to spend a lot of time in

when I was at university, so it was no hardship to revisit old stamping

grounds. Much of the original Leslie Green Leicester Square station

faced still exists, even though the station has a subterranean ticket hall now,

and there’s a steak house restaurant inside most of the original building. On

the opposite side of the Charing Cross Road, on the corner of Charing Cross

Road and Cranbourne Street steps emerge from a rather blocky, 1930s building

next to Wyndham’s Theatre.

Leicester

Square and Covent Garden are well known as the closest stations on the

Underground, although I somehow doubt that they’re the closest street level

station buildings. Nonetheless it didn’t take long to walk to Covent Garden.

When I was a kid, the London Transport collection and museum were temporarily

housed in Syon Park in Brentford, at the end of the E1 bus route from opposite

Elthorne Park. In 1980 though the Museum moved to its permanent home in Covent

Garden, and I dare say that if you’re reading this book, which you are, then a

visit would be something you’d enjoy. The station, at the corner of Long Acre

and James Street, is the original Leslie Green building, and is , in my

opinion, one of the finest of his oeuvre. The corner site gives it a really

pleasing

appearance, albeit that the later building placed on top of the

station does little to enhance its charms.

At this

point I hopped back on the train for the last few stops before the end of this

trip at King’s Cross. The next stop was Holborn. Holborn is, to be

honest, a bit of an ugly duckling in my opinion, although it shows precious few

signs of turning into a beautiful swan. The original station was built by

Leslie Green, however turn of the century planning regulations demanded that

all buildings on Kingsway should be faced with stone, and so there’s none of

the famous ox blood terracotta tiles. In the 1930s modernisation parts of the

Leslie Green facades were replaced by come of Charles Holden’s least appealing

structures. Portland stone and glazed screens in order to accommodate a new

ticket hall and escalators. The remaining parts of the Green station buildings

now house retail outlets.

The opening

of Holborn eventually rang the death knell for the former British Museum

station, which was just a couple of hundred metres away. Prior research showed

that sadly the remains of the station building were demolished in 1989, so

there was no point in me looking for it. Not so the disused Aldwych station. I

mention it here, because there was a short branch line between Holborn and

Aldwych. I did consider walking to the splendidly

restored Leslie Green station

on the Strand, but time was getting on, and not to put too fine a point on it,

I was knackered. I made the decision to try and accommodate the station on a

future trip, but being as its not an any active line now, I wasn’t going to

lose much sleep over it.

My

penultimate stop for the day was Russell Square, and a fine, original

1906 Leslie Green building. It was on the line between Russell Square and Kings

Cross St, Pancras that an explosion, part of a terrorist attack , took place on

a train in 2005. There is a plaque remembering the victims in the station. I

considered calling it a day then and there, but made up my mind to push on to

my original objective.

Apart from anything

else, once I’d ‘bagged’ King’s Cross St. Pancras, it would mean I’d also

have one less stop to worry about on the Metropolitan, Circle, Northern,

Hammersmith and City, and Victoria lines as well.

King’s Cross

is where the Piccadilly Line intersects with the first underground line, since

Kings Cross, which had originally opened in the 1850s, was one of the stations

on the route of the original Metropolitan Railway in 1863. I tend to associate

the main line station building with the name, however the underground station

does at least have a distinctive modern, 21st century entrance,

opened as part of wholescale redevelopments in 2009.

Including

Down Street, Gunnersbury and the stations between Acton Town and Hammersmith

this had been a marathon trip of no fewer than 21 stations.