I start at

Wanstead, bright eyed and bushy tailed. I’ve never travelled on the Hainault

loop before – in fact I’ve never visited any of today’s stations before, and so

we have the excitement of the new if nothing else to sustain us through today’s

trip.

This is an excitement which even the

rather run down and depressed appearance of Wanstead station does little to dampen. I use my phone to google

the station on Wikipedia and I’m surprised to see that it’s a Charles Holden

design. Maybe I shouldn’t be, bearing in mind the tower, which thus far has

seemed a feature only used by Holden and followers of his style. I suppose it’s

the drab colours, and the lack of glazed panels – although there are some on

the other side of the tower that I discover when I take a quick walk around the

outside. Like many Central Line extension stations, this one was started

before, but not finished until after World War two. Before reaching the

station, we went underground, which I really wasn’t expecting this far out of

the centre of London – it’s one thing for a tunnel to continue out into the

suburbs, but quite another for one to start like this.

Thus prepared by the previous station,

I’m pretty ready to identify Redbridge

as the work of Charles Holden. For one thing the red brick tower with the

glazed panels is clearly either the work of Holden, or of someone consciously

using his style. Then there’s the glazed circular booking hall rising above the

entrance – it isn’t as imposing as Arnos Grove, but then few other stations

are. I’ll be honest, it’s a very short journey from platform to street level

considering that this is a ‘tube’ that is deep level station as opposed to cut

and cover, which it feels much more like. Still, let’s concentrate on the

exterior. The canopy with the station name and the entrance underneath it both

gently curve around the booking hall, and all in all it creates a very pleasant

and harmonious appearance. I’m not surprised when Google coughs up the

information that it is in fact a listed building.

I have a lot to say about Gants Hill Station, very little of it

about the exterior though. Basically the station is underground, with entrance

made via pedestrian subways from the roundabout above. That’s it. However,

inside, that’s far more interesting.

This is one

of the last stations designed by Charles Holden. Now, going back to the 30s,

the engineers of the Moscow Underground, now the busiest in Europe, were very

interested in getting ideas from London, and I believe that Charles Holden

himself was consulted. Okay – one result of the Russian engineers’ visits to

London was that the word ‘voksul’ was adopted for metro stations in Russian.

Why? Because, allegedly, they believed that Vauxhall, as in Vauxhall station,

meant station. I’ve yet to find any proof to the contrary of this idea. Holden

himself was inspired by the designs of the station interiors on the brand new

Moscow metro, and this bore fruit with the interior of Gants Hill. The

spectacular barrel vaulted concourse with its art deco uplighters immediately

transports me back to memories of bad spy movies, and I half expect the

gentleman sitting on the other end of the bench to sidle up to me, and whisper

“I hear that in Leningrad the weather will be clement.” in an Eastern European

accident. I’m mildly disappointed when he doesn’t.

However, it’s hard to be disappointed

when the sun is shining outside in the world above, and each station is

offering something different. This is certainly true of Newbury Park station. Now, strictly speaking, the interesting

concrete structure isn’t all the station entrance, but rather a bus shelter

containing the station entrance, and more importantly a grade 2 listed bus

shelter. Now, I’ve no idea how many bus shelters are listed buildings, and if

you know, please don’t write in and shatter my illusions. But I will admit that

when I hear the words ‘listed’ and ‘building’ , then bus shelters are not what

are usually conjured up in my mind’s eye. This is a remarkable structure

though. Designed, not by Charles Holden, unsurprisingly, but Oliver Hill, the

concrete arches hold up a copper covered roof. Now, I’ve very sorry but I do

like a copper covered roof, which probably has something to do with the fact

that the church in which I was christened, St. Thomas the Apostle in Hanwell,

has one. I love the shade of green that copper goes when it reaches a certain

age, as shown by the Statue of Liberty in New York. Many people don’t know that

it’s made out of copper sheeting over a steel frame, and that for years after

it was first erected it was actually copper coloured. Coming back to Newbury

Park, the building was originally designed in the 30s, and seems a remarkably

futuristic design. Oliver Hill himself had designed other wonderful art deco

buildings, including the masterpiece Midland Hotel in Morecambe. Newbury Park

is our second station to have won a design award in the 1951 Festival of

Britain, probably because it wasn’t completed until after World War Two.

If

this part of the Hainault loop had a motto, it might well be – and now for

something completely different, since Barkingside,

the next station, is precisely that. Well, completely different from the

stations that have preceded it anyway. It’s very much the oldest looking

station we’ve encountered so far on this particular trip. Barkingside looks

like an Edwardian national railway station, which is exactly what it started

life as. Google coughs up the gobbet of information that it was opened in 1903,

and probably designed by the Great Eastern Railway’s chief architect, W.N.

Ashbee. What’s not to like here? Well, the concrete rendering which reaches

about a third of the way of the wall of the main part of the building doesn’t

do much to enhance the appeal, but other than that, it’s the kind of thing

that’s always pleasing to my eye. I especially like the cupola on the roof

directly above the entrance. The whole thing is just a little reminiscent of my

primary school. I shouldn’t be really surprised about this, since there was a

spate of school building in England and Wales during the last few years leading

up to the First World War. Both my primary school, and two of the blocks in the

school in South Wales in which I taught for almost 30 years were built in 1913.

And having loved my time in both of these schools, looking at this kind of

architecture brings on a pleasant glow of nostalgia.

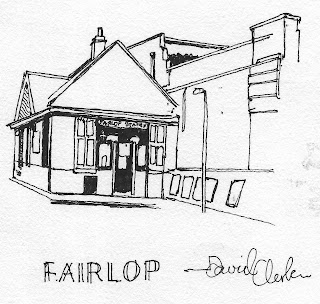

In a way it’s a bit of a shame for Fairlop that I visit the station

straight after Barkingside. I alight under beautiful white painted wooden Great

Eastern Railway canopies, and my expectation is that this is going to be my

second Edwardian railway station in a row. Stepping outside this prediction is

confirmed, and it’s a perfectly nice little station, other than the fact it’s

not as impressive or quite as decorative as Barkingside, which we’ve just

visited. It’s a bit of a shame, since the platforms themselves are amongst the

nicest I’ve seen on the Central Line at all. Everything looks freshly painted.

The iron work holding up the canopies is gorgeous, and for a moment I am

tempted to start acting out a scene from The Railway Children. My Jenny Agutter

impression hasn’t improved with age, I’m afraid.

Well, after such a

run of fine and interesting stations, we had to be brought back to earth at

some time, and Hainault achieves

this. It’s not that it’s ugly, but just that it’s nondescript, which makes it

difficult when you’re trying to descript it. To be fair, it’s difficult to

think of any of the stations I’ve seen which has really benefitted from being

built on the side of a viaduct or a raised section of line. I liked Greenford

for example, but I don’t mind saying it might be even more appealing if it was

completely free standing. Coming back to Hainault, its layout and materials resemble

a Charles Holden entrance hall, but without the benefit of a trademark Holden

ticket hall. The cast iron bridge casts over half of the entrance in what I’d

guess is a perpetual gloom, and although the façade is brightened by the map

and several posters, it doesn’t have any windows, which is a shame. I’ll tell

you something else which is a shame. I always thought that this part of the

world took it’s name Hainault through some connection with Queen Philippa of

Hainault, wife of King Edward III. Apparently not. The spelling was changed

from Hyneholt in the 1600s because of a false connection to her. Hyneholt,

well, I’m not sure about the Hyne bit, but I know from my days studying Old

English at University that holt – as in Northolt – means wood.

Talking of

evocative names, the next station, Grange

Hill, brings back memories of a long running school based TV drama series,

with which it sadly has absolutely no connection. My meagre research has thrown

up a couple of facts about the station itself. Work started in 1938, but wasn’t

completed until after World War II. Heard that before? Of course. Well, how

about this one. The station was hit by a V1 flying bomb ‘doodlebug’ in 1944.

Another thing to add to the long chapter one could write about the London Underground

in wartime. As it stands today, the station looks Holdenesque, ersatz rather

than genuine Holden. I was unable to find out who actually designed it. From

the canopy down, it’s Holden, but the ticket hall rising above and behind the

entrance just doesn’t look quite right. It’s a little too low, and has windows

all around rather than the glazed panels you’d expect from Holden. It’s

perfectly alright as a building, but sadly, by following a Holdenesque plan

this ends up just drawing attention to how it just isn’t quite as nice as a

Holden station.

Well, from ersatz Holden we move now to

another original 1903 building, but this time in a quite different style from

Fairlop and Barkingside. The name Chigwell,

to people of a certain age probably conjures up images of Sharon, Tracey and

Dorian from the long running BBC sitcom ‘Birds of a Feather’ which was set in

Chigwell. This sets me off on a train of thought, as to whether it would be

possible to construct a Comedy Line linking underground stations which have a

connection with comedy programmes. Immediately East Acton comes to mind – it

was nearby Wormwood Scrubs prison which was used for the prison exteriors on

the opening sequence of the 70s sitcom Porridge. Shepherd’s Bush for Steptoe

and Son, and Tooting Broadway for Citizen Smith followed fairly hot on it’s

heels. Reluctantly I drag myself from this pleasant reverie, and file it away

for something to amuse me back on the walk from Roding Park to Buckhurst Hill.

Which is not to say that Chigwell Station is not worthy of attention itself,

because it very much is. Built for the Great Eastern Railway in 1903 I doubt

very much that its changed much in the interim. I can’t help wondering whether

the window frames are original, because they look very plain for the era. That

doesn’t really bother me though, because above the canopy the façade has a pair

of matched dutch gables. I love a dutch gable on an Edwardian or late Victorian

building. So you can imagine, I was like a pig in clover on a recent visit to Amsterdam. Even though I’ve

never visited the station before, if I was to make a list about stations which

have been connected to important things in my life, I would include it, because

this is where Miss Walker lived – the area, not the station – before she became

Mrs. Clark.

I’ve

thoroughly enjoyed my journey around the Hainault loop, but I’m quite happy to

leave the train and begin my walk at Roding

Valley. Actually the sooner the better, since Roding Valley station itself

veers more towards the eyesore than the sight for sore eyes end of the

attractiveness of stations scale. It’s a single story, orange brick building,

and like a lot of the Central line extension buildings it was commenced in the

late 30s, but not completed until the 40s. It certainly looks like a 1930s

building, but with a style such as modernism or art deco, because the buildings

are relatively minimalist in terms of decoration compared to earlier public

buildings, the details are vitally important, and if you get one thing wrong it

can spoil the appearance of the whole building. So having a window boarded up

has a really poor effect on this one.

Thankfully I have

neither the excuse nor time to stand around looking, as I step off towards the

main eastern arm of the Central Line, and the next station, Buckhurst Hill.

There’s a definite spring in my step. The sun is still out, I’ve eaten my

packed lunch, and there’s just five more stations to see before I can add the

Central Line to my completed list. This is a mood which a leisurely half hour

walk, and the sight of Buckhurst Hill

station does nothing to dispel. It’s a very pretty little W.N. Ashbee Great

Eastern Railway station from 1892, the oldest on this particular trip so far.

Certainly when I visited the façade looked to be immaculately maintained with

some gorgeous ornamental brickwork around the shallow arches of the windows.

I’d lay odds that these windows aren’t original though, but hey, you can’t have

everything you want all the time. I’m tempted to make an on the spot sketch of

this little gem like building, but in the end decide that it would be more

sensible to rattle off the next four stations in good time.

Even having

a decent knowledge of the underground, as I like to think I do, I’m still

capable of being surprised by what I see sometimes. My ignorance about this end

of the Central Line, works to my advantage as I exit Loughton station and find I’m absolutely blown away by its design.

It is unlike anything I have seen on any of the trips I’ve made so far, and I

strongly doubt that there is another station on the network that is quite like

it. And yet . . . Then it strikes me, the huge semi circular window above the

entrance, in a rectangular block is a little reminiscent of the façade of

King’s Cross station, albeit that has two windows, and towers at either end.

Here’s the funny thing. The façade of King’s Cross is much, much older than

Loughton, yet Loughton was actually designed by the LNER’s architect, in the

30s, John Murray Easton. King’s Cross, of course, was the main terminus for the

LNER in London at this time. It isn’t what I would call a beautiful station, in

the same way that King’s Cross is not a beautiful station if you’re comparing

it to the yardstick of the Great Midland Hotel looming over neighbouring St.

Pancras. But it is striking, almost magnificent in a way.

This rather makes me fear for Debden station. I just can’t seeing it

living up to Loughton, and so in a way I’m quite pleased when I exit the

building to see that it doesn’t really try. Its façade, which is something of

an elongated shed with a flat roof, is at least enlivened by the raised ticket

hall. However this itself is so low that it tends to peep rather apologetically

over the station canopy. It’s glazed all around rather uninterestingly, and I

can’t help wondering for a moment or two whether it might in fact be a later

addition to the station. Taken all in all, the air of the station is of a

building mumbling ‘nothing to see here citizens, get on with your lives.’

That’s fine by me, and I take advantage of this good advice, since the next

station has one of the more sonorous and intriguing names of any station on the

network, and I’m looking forward to seeing if the station building can live up

to the promise of the name.

Having studied French, after a fashion,

to A Level I’d always pronounced the Bois of Theydon Bois as ‘bwah’. It made sense to me. Bois is French for

wood, and the next station is Epping, as in Forest. Some time ago, though, I

was reliably and authoritatively informed that in the name of the station, Bois

is pronounced to rhyme with noise. As I walk out of the train onto the platform

I find that I am unable to stop myself from singing “Theydon Bois, Theydon

Bois, laced up boots and corduroys.”A gent who looks to be of a similar vintage

to myself smiles at me. For those who aren’t of a similar vintage to myself, I

suggest you ask your parents, or failing that, your grandparents to explain

that reference. Speaking of which, according to Wikipedia, the village has

always been pronounced Boys or Boyce, and derives its name from the family who

held the manor in the 1300s. Interestingly it was the railway which fixed the

spelling at Bois. When the Great Eastern built their station here, the local

parish clerk suggested this would be the best spelling, bearing in mind nearby

Epping Forest. I apologise to those of you reading this who are currently

thinking “I don’t need to know that, kindly leave the stage” but the fact is

that I love finding out these little obscurities.

As for the

station building itself, I can’t for certain say when it was built. Looking at

it, I somehow doubt that it’s the original, since the window frames and the

ornamental brickwork on some of the corners suggest a similar vintage to the

1903 stations we saw on the Hainault loop. It’s a pleasant place, although I

can’t help wishing that the two storey building on the right had been left its

original red brick rather than being painted with the brilliant white that it

sported during my visit.

Epping

is a name I once used in a long poem I wrote at University. Without going into

too much detail, Dream Vision Poetry was a genre of poetry practiced in the 14th

century by Chaucer and some of

his contemporaries. It inevitably involved the voice in the poem being spirited

away in a dream, often to an idyllic, Eden-like setting which we would call by

the latin term – locus amoenus. Got that? Okay, so in this poem I wrote,

“I looked to

try and see where I was stepping.

I guessed locus

amoenus, maybe Epping.”

This was

more for the rhyme than anything else, since I’ve never been to Epping before

and have absolutely no idea whether it’s a locus amoenus, a locus horribilis,

or something in between. Actually, that’s still true, since I confine my

perusal of the surroundings to the station buildings itself. They’re rather

nice, rather reminiscent of Theydon Bois, although something of a mirror image

since the two storey wing is on the left this time. Once again, I’m unable to

conjure up any specific dates of construction, or architects’ name on the

phone, but as with Theydon Bois I’m pretty happy that it’s Edwardian or late

Victorian, which would make it originally a GER station. Which is where the

line ends, or at least, where it has ended since 1994. In that year, London

Transport ended the single track service between Epping and Ongar. I was always

intrigued by this on the map, as I have memories of it being represented by a

read and white line, and looking for all the world like a horizontal barber

pole. The memory my be cheating me on this one, I admit. There have been short

lived attempts to run services by private companies from Epping to Ongar since,

but since that’s not part of the underground network now, I don’t concern

myself with it.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Three cheers

for the Central line! The longest journey you can make without changing trains

anywhere on the network is from West Ruislip to Epping, which is slightly more

than a whopping 34 miles. This makes me even happier that I didn’t make a rule

that I have to walk between every station. If that were the case then this

challenge would take years rather than the months I’ve allotted for it. It has

the 4th greatest number of stations, after the District, Piccadilly,

and the Northern line which boasts just one more. Not including Osterley and

Spring Grove, which is no longer a station, I’ve now sketched 155 stations.

That’s 57.4% or 31/54. I think a small celebration might be in order.

It’s fairly

obvious which line I need to tackle next. There are 50 stations on the Northern

Line, only five of which I’ve already visited on other lines. That splits

nicely into three trips, and more importantly, it should take me to 200,

leaving only a measly 70 to do on the remaining lines.