If you've recently checked out my sister blog - my main art blog, then you'll probably already know all about this. Still, just in case, what with not being able to get out and about, I'e been making a virtual tour of some of Britain's most beautiful buildings in sketches. Here's what I've done in the last fortnight or so:-

Experiences of an urban sketcher based in South Wales - does exactly what it says on the tin. All images in this blog are copyright, and may not be used or reproduced without my permission. If you'd like an original, a print, or to use them in some other fashion, then email me at londinius@yahoo.co.uk.

Friday, 21 August 2020

Not actually Urban Sketches at all . . .

Chester - A3

Durham A4

St. Paul's A4

Tower Bridge A3

Newcastle Tyne Bridge A3

Edinburgh Cityscape A3

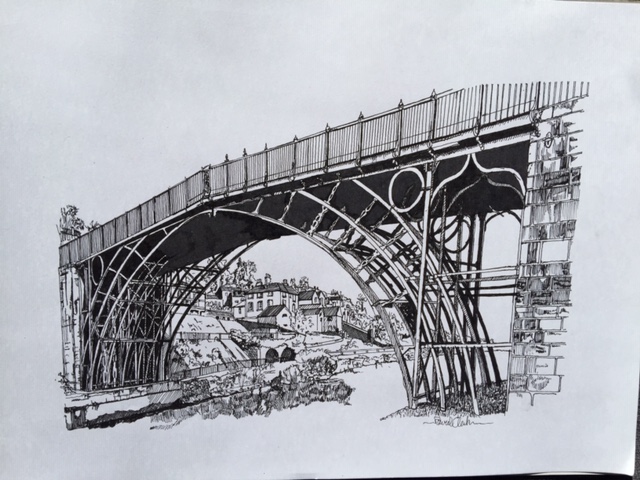

Iron Bridge Coalbrookdale A3

Sunday, 9 August 2020

Wednesday, 29 April 2020

British Illustrators 40: William Hogarth and Gin Lane

To my mind, William Hogarth was quite simply one of the greatest English artists. He’s best known for several series of paintings, such as “The Rake’s Progress”, and for engravings such as this one, “Gin Lane”. Hogarth’s depictions, and implicit moral commentaries upon, the London life he saw around him have given rise to the adjective Hogarthian, descriptive of the immorality of the Georgian era of rakes and harlots.

The engraving I’ve copied, “Gin Lane” is one of Hogarth’s most famous. It’s actually one of a pair he made in 1751, the other being “Beer Street”. Taken together they are a commentary on the evils of gin drinking, compared to beer drinking. In late 17th and early -mid 18th century London huge gin consumption, caused by a variety of factors, was seen as responsible for an array of social problems, as the urban poor sought relief from poverty through the escape offered by cheap gin. In the picture itself we can see the child falling to its death, a victim of starvation, mob violence and homes falling to pieces.

I’ve always loved Hogarth anyway, but about a decade ago, while researching my family history, I found that my great, great, great, great, great grandfather was a cartoonist and engraver called Philip Dawe, who was a pupil of William Hogarth.

Tuesday, 28 April 2020

British Illustrators 39 - Robin Jacques and Gullivers Travels

Robin Jacques, a very prolific British illustrator from the 1940s until his death in the 1990s, was ironically far less well known in the UK than his sister, the actress comedienne Hattie Jacques. To most Brits in their mid 50s and older, she is one of a handful of actors well remembered for a long running series of comedy films called the Carry Ons.

Robin Jacques was self-taught, and in his teens he began working as an artist in the advertising industry. He went on to work as Art editor for magazines, and to teach art, as well as illustrating well over 100 children’s books. His signature style involved a stippling technique, which is highly effective, harking back as it does to almost a Victorian engraving style. I can vouch for the fact that it is exceptionally time consuming, though!

Monday, 27 April 2020

British Illustrators: 38 Dave Gibbons and Watchmen

Together with British writer Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons created what I feel is one of the greatest graphic novels of all time, “Watchmen”, which was later made into a film. Although the film deviated a little in script from the story, visually it was incredibly faithful to Dave Gibbons original illustrations, which pretty much says all you need to know about their effectiveness.

Dave Gibbons first came to prominence working for the seminal British comic of the 70s, 2000 AD. The best known serial of this comic was Judge Dredd, which later became a couple of lacklustre movies. I first came to know his work on the comic strips within the early issues of Doctor Who Magazine. In the early 80s Dave Gibbons went to work for DC Comics, which led to collaborations with fellow Brit Alan Moore, and eventually the masterpiece that is Watchmen.

Sunday, 26 April 2020

British Illustrators 37: William Stobbs and Scottish Folk Tales

William

Stobbs was a Greenaway Medal winning artist and illustrator throughout the

second half of the 20th century. During the 1950s he was the head of

the design department of the London School of Printing and Kindred Trades, and

later on became the principal of the Maidstone School of Art.

He won the Greenaway Medal in 1959 and unusually two of his books were cited – an edition of a short story by Chekov (the Russian writer, not the USS Enterprise’s helmsman) called Kashtanka, and a book called A Bundle of Ballads

This is actually a copy of an illustration he made for a book of Scottish Folk Tales, and it just really does it for me. Who wouldn’t want to read a story which has an illustration like this accompanying it?

He won the Greenaway Medal in 1959 and unusually two of his books were cited – an edition of a short story by Chekov (the Russian writer, not the USS Enterprise’s helmsman) called Kashtanka, and a book called A Bundle of Ballads

This is actually a copy of an illustration he made for a book of Scottish Folk Tales, and it just really does it for me. Who wouldn’t want to read a story which has an illustration like this accompanying it?

Friday, 24 April 2020

British Illustrators 36: Charles Keeping

Charles Keeping was another Greenaway Medal winner. Charles Keeping first came to prominence illustrating some of the historical novels of Rosemary Sutcliff. He actually won two Greenaway Medals, one for his own story, “Charley, Charlotte and the Golden Canary”, and one for his illustrated edition of Alfred Noyes’ poem “The Highwayman”.

Keeping served in the Royal Navy during World War II, having joined at the age of 18. After the war he studied Art part time and then full time, and from the 50s until his death in 1988 he worked for many outlets, including Punch. In 1956 he was commissioned to illustrate Rosemary Sutcliff’s “The Silver Branch”. His success saw him commissioned to illustrate others of Sutcliff’s novels and also those of Henry Treece and others.

I’ve chosen to copy an illustration Keeping made for an edition of “The Jungle Book”. The most complicated parts were the trees and foliage in the background. Two different graphite pencils – a 6B for lighter shading and a 2B for darker shading – really gave this texture – it looked nothing like as good with just the ink marks.

British Illustrators 35: Sir Frank Brangwyn

Largely self-taught Sir Frank Brangwyn produced over 12000 works during his lifetime in his career as painter, print maker, designer and illustrator between the end of the 19th century, and his death in 1956. By the middle of the 20th century he was one of the most popular and successful British artists of the time.

In the nearest city to where I live in Wales, Swansea, there is a large gallery and performance space named after him, the Brangwyn Hall. It is so called because it contains a number of murals he painted which were commissioned for, then rejected by the House of Lords in Westminster. Their loss was Swansea’s gain.

In 2006, when I was staying in Leeds, Yorkshire, to take part in a popular television quiz show, there was an exhibition of Brangwyn’s work in Leeds’ magnificent Town Hall. I knew next to nothing about him, but was bowled over by what I saw, not just his illustration work, and his graphic work, but also by some of his incredibly vibrant and joyous paintings. This is a copy of his painting “A Street Scene in Tangiers”. The original is an oil painting, while I used acrylics, and a canvas only about half the size of the original. It must have taken well over 10 hours for me to paint this, but I thoroughly enjoyed the process.

Thursday, 23 April 2020

British Illustrators 34: Judith Kerr

The late

Judith Kerr, who passed away in 2019, will always be remembered for the ever

popular “The Tiger who came to Tea”. She also created the Mog series, and wrote

“When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit”. She had personal experience to draw on for

that book, since she was born in Weimar Germany, but her parents both knew that

Nazi success in the 1933 elections could spell potential disaster for a Jewish

family such as themselves, and the family moved to France before settling in

Britain.

Judith Kerr became a naturalised British subject, and married Nigel Kneale. That name might not mean a great deal to you if you’re not British or of a certain age, but he wrote “Quatermass” which was the first TV science fiction serial to gain mass appeal in the UK, and led to 3 spin off films. Their son, Matthew Kneale is no mean writer himself. He wrote an excellent historical novel “English Passengers” which I can thoroughly recommend. Coming back to “The Tiger Who Came To Tea”, it was published in 1968, and has remained hugely popular ever since. Judith Kerr created the story after a visit to the zoo with her three year old daughter. It took her a year to make the book, and it has since become one of the best selling children’s books of all time.

Judith Kerr became a naturalised British subject, and married Nigel Kneale. That name might not mean a great deal to you if you’re not British or of a certain age, but he wrote “Quatermass” which was the first TV science fiction serial to gain mass appeal in the UK, and led to 3 spin off films. Their son, Matthew Kneale is no mean writer himself. He wrote an excellent historical novel “English Passengers” which I can thoroughly recommend. Coming back to “The Tiger Who Came To Tea”, it was published in 1968, and has remained hugely popular ever since. Judith Kerr created the story after a visit to the zoo with her three year old daughter. It took her a year to make the book, and it has since become one of the best selling children’s books of all time.

Tuesday, 21 April 2020

British Illustrators 33: Edmund Dulac and The Little Mermaid

Edmund Dulac was actually born

French, but moved to England in his early 20s, and became a British citizen in

1912.

On arrival in London, Dulac was

commissioned to illustrate Dent’s edition Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. He

worked for the Pall Mall Gazette, and then was commissioned by Hodder and

Stoughton to illustrate a number of books, including the works of Hans

Christian Anderson, from which I have tried to copy an illustration he made of

the Little Mermaid.

When I look at Dulac’s illustrations

for this and other books I am struck that he works in a similar style to his

contemporary Arthur Rackham. After the first World War there was much less

demand for illustrated picture books of the style he had been producing before,

and so he moved into other areas, such as newspaper caricatures, portraiture

and theatre design. Like later illustrators Ralph Steadman and Gerald Scarfe,

Dulac also illustrated postage stamps for the Royal Mail.

British Illustrators 32: Edward Burne Jones

Burne-Jones is associated with both

the Pre Raphaelite-Brotherhood, whom he admired tremendously in his early

years, and also with the Arts and Crafts Movement. He was a pre-eminent artist

in the field of stained glass, and also a founder member, with William Morris,

or Morris’ decorative arts firm. As well as his own paintings, and his work in

the field of stained glass and of design, Burne-Jones also illustrated a number

of works for Morris’ Kelmscott Press. In this illustration, copied from an

illustration of the Kelmscott’s Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Burne-Jones’

distinctive almost medieval style is a perfect match for the subject matter.

Burne-Jones was very influential on

the next generation of artists and illustrators in England as well. The teenage

Aubrey Beardsley made a speculative visit to Burne-Jones’ home, and showed him

sone of his sketches. Burne-Jones allegedly told him that he was not in the

habit of advising young people to become artists, but he had no choice but to

do so in Beardsley’s case. Quite right too. In the 1890s he became something of

a pillar of the establishment, being made a Baronet (A baronetcy is a

hereditary knighthood – an ordinary knighthood passes away on the death of the

recipient.)

Sunday, 19 April 2020

British Illustrators 31: Victor Ambrus

Off Prompt: British Illustrators 31:

Victor Ambrus

Victor Ambrus is another two-time

Greenaway Medal winner. Victor Ambrus was born and grew up in Hungary, where he

was studying in the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts during the failed 1956 revolution

against the Soviet backed regime. In December he and other students fled first

to Austria, then to Britain, where he hoped to study in the tradition of great

British illustrators such as E.H. Shepard, John Tenniel and Arthur Rackham.

Hungary’s loss has indisputably been Britain’s gain.

Victor Ambrus has illustrated a great

many children’s books, both fiction and non-fiction. I chose this sketch

because it illustrates two really important themes in his work, horses, and the

historical past. For several years Victor Ambrus’ illustrations formed an

important part of the popular British Archaeology documentary series Time Team,

in which a group of archaeologists, surveyors and archivists would be given

three days to carry out an investigation of a historical – or in some cases

pre-historical – site, and their discoveries would help inform the

illustrations which Victor would make of the site in its former heyday.

British Illustrators 30: Gerald Scarfe and The Wall

Gerald Scarfe is another great British illustrator whom I’ve chosen to include even though he’s most definitely not known for illustrations to children’s books.

Gerald Scarfe at one point studied at the same time as Ralph Steadman at East Ham Technical College. The two fell out when working for the Daily Mail. After a brief career in advertising, Gerald Scarfe became a savage political cartoonist, possibly the best known in the UK. Like Steadman, he has worked for a wide range of publications in the UK and the US, he has designed postage stamps for the Royal Mail. He famously worked with the band Pink Floyd on the album “The Wall”, and this is why I have copied one of the illustrations he produced for the album. On my 17th birthday I saw Pink Floyd performing The Wall at Earl’s Court in London, and Scarfe’s work in the form of animations, projections, and huge inflatables, played a crucial part in the performance and the experience. If you look at the picture and the words “You, yes, you. Stand still laddie!” come into your mind, then you’re probably a Floyd fan as well.

Friday, 17 April 2020

British Illustrators 28: Carl Giles and Grandma

I haven’t chosen Carl Giles because he illustrated children’s books. He didn’t. Carl Giles was actually a political cartoonist in the UK’s Daily Express newspaper from the early 1940s until 1989.

So why am I including him? Well, Giles’ popularity became so great that from 1946 onwards, Giles cartoons for the previous year were published in an annual. I first encountered them as a kid, when I read one in a doctor’s waiting room. I didn’t get a lot of the jokes, not knowing the context. However I was captivated by the images. In many of his cartoons, Giles used his fictionalised ‘Giles’ family, and the grandmother, “Grandma” became something of a national institution. So much so that there is actually a statue of Grandma in Ipswich, Giles’ adopted hometown. In many English households the arrival of the Giles annual became something of a Christmas institution. I learned a lot about England in the late 50s and early 60s, before I was born, from reading old Giles annuals.

I had to copy Grandma, of course, but a typical Giles cartoon has much more to it than one or two characters. There’s often a whole other level of humour going on in the background, and they’re the sort of thing you can look at two or three times, and still see something new in them.

Wednesday, 15 April 2020

British Illustrators 27: Ralph Steadman

Like Sir Quentin Blake and Helen Oxenbury, Ralph Steadman is still very much alive. Unlike them, he isn’t best known as an illustrator of children’s books. As early as his student days in the 60s, Ralph Steadman was contributing to satirical magazine Private Eye, and the Daily Telegraph in the UK, and the New York Times and Rolling Stone in the US.

Since then he has completed a huge body of work including satirical and political cartoons, album covers, posters for the Royal Shakespeare company, postage stamps for the Royal Mail, and also illustrations for editions of books including Treasure Island and Alice in Wonderland – two of my favourite children’s books of all time.

I agonised for a while over which illustration I wanted to copy, but in the end I decided that Ralph Steadman’s anarchic, almost explosive style lends itself more naturally to Alice in Wonderland. (Although I also love his Treasure Island illustrations too!)

British Illustrators 26: Helen Oxenbury and Alice Through the Looking Glass

Helen Oxenbury is a British illustrator of children’s books, who has twice won the Greenaway medal. Nobody has yet won it three times. She spent some of the early part of her career working in theatre design, and turned to illustrating children’s books after marrying fellow illustrator John Burningham.

I’m familiar with Helen Oxenbury mostly through books I’ve read with my children when they were young, and with my grandchildren. I’ve chosen to copy one of her illustrations from Alice through the Looking Glass. I’ve written before about my love of and fascination with the Alice books. While I will always love John Tenniel’s original illustrations, and they will always be the archetypal images of the books as far as I am concerned, Helen Oxenbury’s illustrations brought something new and interesting to the stories for me. Her Alice is a modern girl, which if anything makes her seem even more out of place amongst the strangeness of Wonderland and the Looking Glass world. Like Sir Quentin Blake, Helen Oxenbury is still going strong.

British Illustrators 25: Kate Greenaway and The Pied Piper of Hamelin

Kate Greenaway was amongst the most popular British illustrators of the Victorian period, and her popularity has never really diminished since. When, in the 1950s, the Library Association decided to inaugurate an annual prize for distinguished illustration in a book for children, it decided to name the medal after Kate Greenaway.

The daughter of an engraver, Kate Greenaway had to battle against the prejudice of the time in order to first study art, and then to make a living from it. For example, women were banned from attending life drawing classes. She first tasted commercial success designing greetings cards for printer Edmund Evans. In 1879 she wrote and illustrated a book of verses,”Under the Window” , which was a best seller, and from then until her death in 1901, aged 55, she remained one of the most poplar illustrators and designers in Britain.

This is a copy of an illustration she made to Robert Browning’s poem “The Pied Piper of Hamelin”.

British Illustrators 24:Randolph Caldecott and The House that Jack Built

It’s confession time. I hadn’t even heard of Randolph Caldecott until I was researching Kate Greenaway for a future post. Randolph Caldecott’s name came up several times, as one of Kate Greenaway’s very gifted contemporaries. Although born in England in Chester, it seems that he is more honoured in the USA, where the Caldecott medal, named in his honour, is presented for the most distinguished American picture book for children of the previous year.

Randolph Caldecott began as a clerk, but sent sketches and illustrations to many magazines and had them published. He hadn’t necessarily planned to become mainly an illustrator of children’s books, when Edmund Evans, a colour printer, having lost the services of Walter Crane engaged him to produce illustrations for two Christmas books. One of these was The House that Jack Built. So successful were they with the public that Caldecott would go on to produce two more books every Christmas until he died in 1886 at the age of 40. His health had always been poor, and he actually died in St. Augustine, Florida, where ironically he had taken a trip to help improve his health.

Contemporaries praised Caldecott for his simplicity, and I can echo this. The lack of Victorian fussiness about his work makes it seem far more timeless than some of his contemporaries.

Saturday, 11 April 2020

British Illustrators 23: Hablot Knight Browne "Phiz"and "The Pickwick Papers"

Off Prompt: British Illustrators 23: Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) and The Pickwick Papers

You might not have heard how Phiz – the pen name of Hablot Knight Browne – came to illustrate “The Pickwick Papers” and a further 9 of Charles Dickens’ books. The idea behind “The Pickwick Papers” was that it would be a series of illustrations by famous artist of the day Robert Seymour, and the young up and coming Dickens would write an accompanying text. Originally Seymour’s illustrations were supposed to be the driving force, and the story would be about the Pickwick club’s sporting misadventures, this genre being popular at the time. Seymour committed suicide after making the first 7 illustrations, before the second part was complete. Although Robert Buss produced a couple of illustrations to complete the second part, Dickens was looking for a permanent illustrator for the rest of the Pickwick Papers. On the same day he looked at work by Browne, and a certain William Makepeace Thackeray. At this point Thackeray believed he would find success with his pictures, and it was ten years before he really struck gold with his novel Vanity Fair. Coming back to Browne, Dickens instantly saw what Browne could bring to the novel, and they began a partnership and friendship. Browne adopted the pen name Phiz, because it went well with Dickens’ own early pen name, Boz.

I suspect that what attracted Dickens to Browne’s work was his great ability with character, Even if you’d never read “The Pickwick Papers” you could probably tell a lot quite accurately from the characters in this illustration. The fact that this is just a detail from the original suggest that Browne had his work cut out making the illustrations. This took literally hours, and I was using modern equipment, and just copying part of the original. The work of making the illustration, then etching it onto copper boggles the mind, especially when one thinks that Dickens, who was a workaholic, expected exacting standards of those who worked for him.

Friday, 10 April 2020

British Illustrators 22: James Gillray and The King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver

Okay, so once again we’re not dealing with an illustrator of children’s fiction. However we can justify James Gillray in the same way that we justified Aubrey Beardsley – namely, that he was brilliant. However I think we can also justify Gillray in the sense that you can draw a direct line of descent from 18th century cartoonists like Gillray to cartoonist illustrators of the next generation like George Cruikshank, to illustrators like Phiz, then Tenniel, and so on.

From the late 1770s until his death in 1815, a matter of days before the Battle of Waterloo, Gillray’s cartoons described the great political evets of the day with biting satire. Amongst his favourite targets were George III, seen in this cartoon, and George’s oldest son, the Prince Regent. I chose this cartoon, not because I think it’s the cleverest he ever made, but because it shows his great influence. By all accounts, Napoleon Bonaparte was actually a man of average height for his time. However Gillray, in prints such as this one, and another in which he is carving up a plum pudding in the shape of the globe with Pitt the Younger, depicts Napoleon as a small figure, and this popular idea of Napoleon as a classic example of small man syndrome which has stood the test of time. The title refers to the second of Gulliver’s Travels in which Gulliver visits Brobdingnag, where he finds himself among giants.

Former Underground Stations

So, we ended

the challenge with me thinking that we’d see about whether it was all over –

even before I’d finished drinking the champagne. If you’re old enough to have a

good enough memory of Tom and Jerry cartoons, I invite you to recall that a

number of times our protagonists would find themselves on the horns of a

dilemma. This would be represented by a good angel version of either Tom or

Jerry, and a naughty devil version appearing on either shoulder, both trying to

persuade the original to decide on their preferred course of action. This is

how I’d like to present the dilemma which now faced me as I was driving us home

on the Sunday morning. Basically, the little devil told me that I’d done the

job, and that was that. The little angel reminded me that I’d passed a number

of disused station buildings – or passed under them, and I hadn’t sketched any

of them, and shouldn’t I take care of this oversight? Little devil just

laughed, but it was a nervous laugh, and when he was unable to come up with an

argument against doing so, he promptly vanished with a puff of indignation.

·

I will make one final trip, during which I will

try to make a sketch of all the former station buildings I saw during the

challenge, and as many others as is feasible.

·

Only stations which were once part of the lines

as they exist now count. Stations from branches or arms which no longer exist

as part of the Underground do not count.

·

Except Aldwych. (since it’s easy to get to in

Central London)

·

Only stations with street level buildings

remaining count.

·

I reserve the right to change, revise and cancel

existing rules as I feel like it, and to create new ones on an ad hoc basis.

One trip

then, and an itinerary consisting of:-

Osterley and

Spring Grove

South Harrow

Brompton

Road

Knightsbridge

Hyde Park

Down Street

Aldwych

Mark Lane

York Road

Euston

South

Kentish Town

Marlborough

Road

The problem

with the rules was, of course, the fact that they didn’t really give me a clue

about how I was going to persuade Mary to give her blessing to another trip. So

far it had taken up a fair proportion of our free time for over 3 months. With

the best will in the world it was going to be hard to talk her into giving her

blessing for one more trip which wasn’t even part of the original challenge. By

rights I ought to leave it for a good year or so before broaching it.

I need to be

careful how I phrase this next bit. I would never want to give the impression

that I look on my mother in law having a bout of ill health as a slice of good

fortune on my part. My in laws – Jen and Mary’s step dar John live in the

Alicante area of Spain, and both have had their health issues over the last few

years. When it gets particularly difficult, Mary will often fly out to help

them for a week or a fortnight. Within a month of our return from the final

challenge trip, Jen was hospitalised for a week, and so Mary flew out to help.

If me not

doing this additional trip could have had any bearing on Jen’s illness, or made

things easier for Mary and John, then of course I wouldn’t have done it. But in

all honesty it could make no difference to them at all. So. . . play ball.

This was my

planned itinerary. Having to do the two western arms of the Piccadilly is a

pain, but the simplest way will be to forget about the rule, from the challenge,

of not doubling back on myself in the same trip. So I start at Osterley and

Spring Grove, catch the Piccadilly to Acton Town, and change for South Harrow.

Then it’s back along the Piccadilly all the way to Brompton Road. In a very

doable walk, I can take in Brompton Road, Knightsbridge, Hyde Park Corner and

Down Street. A short walk to Green Park station, and then a ride to Holborn

will put me just a few minutes’ walk from Aldwych station. Another brief walk

to Temple station puts me on the District or Circle Line which will give me a

ride all the way to Tower Hill, from which it’s just a sort step to Mark Lane

station and back. From Tower Hill the Circle will get me to Kings Cross. It’s a

round trip walk of about 25 minutes to York Road station and back, but only a

short ride to Euston. Once I’ve bagged the disused Leslie Green station

building there, then it’s up the Northern line to Kentish Town, and a walk to

South Kentish Town and back. Then it’s back to King’s Cross, and the

Metropolitan to Finchley Road. A walk to Marlborough Road, and then relax. Simples.

I do have a

liking for second hand bookshops, and it’s only with reluctance that I tear

myself away from the place to walk back towards Osterley station. However, I know that I must. The longest walk

today is probably only going to take me about half an hour, but there’s several

walks to do, since most of our disused stations aren’t conveniently situated

right next to an existing station.

Back on the

train, I come up with a rather silly London Underground station trivia

question. Namely – which of the cardinal compass points occurs most often in

the names of tube stations. My best guess is North. When I get to Acton Town I

google this, and find out that East is very much the runt of the litter with a

mere 8, while West does surprisingly well with 10, just being pipped by North

and South which both have 11. However, once we add South Kentish Town as a tie

break, that just gives it to South for me. So South progresses to the second-round

stages of my new game of Tube station name world cup.

The semi-finals

and the finals have to wait as we alight at South Kensington.

2012. On a whim, I checked out how much it costs for a double room for one night. Let’s just put it this way, I can’t afford it. Still, I applaud the place for preserving the station façade by building the hotel around it as much as they have, even though I can’t help wishing that the previous occupants, Pizza on the Park, were still there. I’m hungry, and it’s only mid-morning, but stuff it, I’m not going to hang about with my packed lunch today.

We've just had three disused Leslie Green stations in a row, and we're not even close to be done yet. It's only a brief walk to a disused station that I did actually visit way back on my third Piccadilly Line trip months ago.

There are

websites dedicated to Former London Underground Stations, and pretty much

everyone I’ve seen features our next station, Down Street. Bearing in mind its

history, that’s not at all

surprising. Repeating what I wrote after my previous visit - Down

Street was originally a stop between Green Park and Hyde Park Corner, which

opened in 1907, and closed, due to lack of use, in 1932. The Leslie Green

station building still remains, but probably wouldn’t be much remembered other

than for the fact that it was used by Winston Churchill as a bunker during

World War II. Apparently, it is possible to access the underground levels of

the station, and occasionally London Transport has allowed the privileged few

to do just that. Last time I was here I bought a paper, but today I’m even more

of a man on a mission, and I take the necessary photos for the sketch, and then

stride onwards to Green Park station.

This gives

me time to work out how the semi-finals of Tube station world cup pan out.

Streets and Lanes United comfortably beat South Wanderers, while the all-conquering

Natural Features All Stars trounce Park Rangers. In the final, it’s a very

comfortable win for Natural Features, while Park Rangers wins the third place

play off and will therefore not have to pre-qualify for the next tournament.

Our last

five stops have all been Leslie Green stations. Now, though, after walking to

Temple Station, I take the District to Tower Hill, where it’s just a short walk

westwards to Mark Lane station, which was later called Tower Hill until

it was replaced by the current station in 1967. There’s little to show

I have mixed

feelings, and I’ll try to explain. I think Leslie Green stations are beautiful,

and in an ideal world, all of them would still be standing. It’s not an ideal

world, though. The point of conservation and preservation is to protect the

best of our shared cultural heritage, yes. However, it isn’t to preserve them

in aspic. Yes, there should be debate, serious and prolonged if necessary,

every time a building like this is considered for demolition. Development, and

redevelopment, is a fact of life in any city, and even more so in a city like

London, and if you look at the history of the city, it always has been.

Otherwise there’d still be an amphitheatre where the Guildhall still stands,

for example. And a gallows instead of Marble Arch. And fortified gateways

blocking major roads in and out of the Square Mile. I absolutely love museums,

but I’m not sure it would be a good idea to try to live in one.

What we have

to ensure, though, is that development does not impoverish the area, as

happened so much from the 60s right through until the end of the 20th

century. Or to put it another way, if you’re going to take away a building like

this, then make sure you put something worthwhile in its place., instead of

something which a mere 20 years after its built causes those who even notice it

to wonder ‘ what were they thinking?’ If nothing else, it must make each of the

Leslie Green stations still standing more valuable to all of us.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

That really

is that. As I drive past Boston Manor, I am absolutely certain that my

challenge is at an end. I stop at Leigh Delamere and I’m still resolved to

leave it there now. I know that there are still a significant number of disused

station buildings that I haven’t visited which are outside the current reach of

the network. Then there’s the Overground. And the DLR. And that’s absolutely

fine. Maybe there’s a challenge for somebody else, maybe there’s a challenge

for me to take up in a few years’ time.

I suppose

it’s normal, on completion of a challenge’ to look back and reflect on what

you’ve achieved. Bit difficult in my case, to be honest. What have I got out of

it? Er. . . about 300 sketches and that’s about it. Well, that and the credit

card bills for the fuel and topping up the nectar card. Has it increased my

love for the tube? Probably not. What it has done, though, is booted it into

the 21st century. Prior to this my love of the tube was mostly

fuelled by nostalgia, and memories of good times from my childhood and youth,

before marriage and real adulthood. I can honesty say though that my rose

tinted specs have been removed by this trip, and I have a clearer view of what

the tube really is. It is dirty. It is smelly. It is crowded, and at times

perplexing and frustrating. It is also utterly wonderful. The wonder of the

tube isn’t that it occasionally provides a less than perfect service – the

wonder of it is that it works as well as it does. When it comes to the

stations, the underground network can be justifiably proud of the contribution they

have made to the architectural heritage of the capital, and in the newest

stations there’s evidence of this safely continuing into the future.

Thursday, 9 April 2020

British Illustrators 21: Aubrey Beardsley and Salome

Off Prompt: British Illustrators 21: Aubrey Beardsley and Salome

OK, Salome was very much not a children’s book. So how does Aubrey Beardsley qualify? Well, I can stretch the point because although Aubrey Beardsley was very much not a children’s illustrator, he did at one point illustrate an edition of the 1001 Arabian Nights. And furthermore. . . he was a genius in my book. Effectively his career lasted about 6 years, before his tragic early death from tuberculosis at the age of 26. For the later part of that career he was often vilified. However his work is now more popular than ever, and his influence on artists, and graphic designers since the 60s has been frankly immense.

Looking at this famous image you can see some of the hallmarks of the Art Nouveau style of which Beardsley was an innovator – the elongated liquid forms, for example. But look at the way he uses monochrome – this was not years ahead of his time, but decades. I first came to know of Beardsley and his work when I was 17, and studying my English A levels. (A levels are/were the qualifications you needed to pass in England and Wales in order to gain a place to study at University). One of my fellow students was not, frankly, great at English, but he was a superb artist, and he told me about basing his final project on Beardsley. When I researched this name which I knew nothing about, I too fell instantly under his spell.

British Illustrators 20: Mervyn Peake and Treasure Island

Mervyn Peake is another of our great writer-illustrators. Today he’s best remembered for his three dark, gothic Gormenghast fantasy novels. I thoroughly enjoyed both “Titus Groan” and “Gormenghast”, the first two novels of the series, although I really couldn’t get on with “Titus Alone”, the final novel of the series. However, focusing on Mervyn Peake as an illustrator, I’ve chosen to copy one of his brilliant illustrations for Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island.

Mervyn Peake was actually born in China, of British parents, although he left China never to return when he was 11 years old. He trained as an artist in the Royal Academy Schools, but by his early 20s he was already writing poetry as well as painting. In a varied career, Peake actually designed the logo for Pan Books, a popular paperback imprint. The story goes that he was offered the choice of either a flat fee or a royalty of a farthing (1/4 of an old penny) per book, and on the advice of Graham Greene turned down the royalty and thus lost a small fortune. Peake was a lifelong lover of the work of Robert Louis Stevenson, and his illustrations for Treasure Island are, in my opinion, among the finest ever made of a book which has always been a favourite of mine as well. It took ages to make this copy. Peake’s style in this illustration eschews long continuous lines – apart from in the shading of the background.

Wednesday, 8 April 2020

British Illustrators 19: George Cruikshank and Oliver Twist

Contrary to what you might think, not

all of Charles Dickens’ novels were originally illustrated by Phiz (real name

Hablot Knight Brown). His second novel, Oliver Twist, was illustrated by George

Cruikshank, a very well-known illustrator of his day.

We could argue about whether it’s

fair to put Dickens’ novels into the category of children’s literature.

Certainly his contemporary audience included all ages and pretty much all

classes. Leaving that to one side, though, I’ve been a lover of Dickens ever

since I first read “David Copperfield” as a kid. It took me longer than any

other novel I’d read up to that point, but it was well worth it.

As for George Cruickshank, in the

early part of his career he was pretty much a successor to political cartoonist

James Gillray. When he illustrated Dickens “Sketches by Boz” he was far more

well known and popular than the author, although Dickens’ success would come to

far outstrip Cruikshank. In later years Cruickshank claimed credit for much of

the plot of Olver Twist, which frankly seems unlikely. It’s worth noting that

he waited until Dickens had died before writing a letter to the Times to claim

as much in 1871. Cruikshank is interesting to me because he provides a link

between the cartoonist illustrators of Gillray’s generation, and those of

Tenniel’s generation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Catching Up . . .

Been a while, hasn't it? Don't worry, I haven't given up sketching. No, I just haven't got round to posting anything. Now, ...

-

Richmal Crompton was a teacher in south east London who took up writing seriously in the early 1920s after polio forced her to give up h...

-

Steel hulks Unregarded, unloved Waited for salvation From the gas axe, and blow torch. And saviours came. My first visit to Wales in...

-

Life is a like a Ferris Wheel Ups and downs And going round and round in circles. This is the biggest sketch I've done in t...