The

Central Line began life in 1900 as the Central London Railway, and it was the

third deep level tube line in Central London. Originally it rank from Bank in

the east to Shepherd’s Bush in the west. As the Central London Railway it only

extended one further stop east to the Liverpool Street mainline terminus, but

by 1920 it had reached as far west as Ealing Broadway. By this time the company

had been taken over by the UERL, although the company was kept legally separate

from the parent company.

Under the

LPTB (London Passenger Transport Board) the plans to extend the line at both

ends were formulated, but the extensions as far as West Ruislip and Ongar were

only completed by the end of the 1940s, having been substantially delayed by

World War II. The line from Epping to Ongar was discontinued as part of the

Underground network I 1994, although it has been run as a heritage railway at

times since. The Central Line has fewer stations than District, Piccadilly and

Northern Lines, but it is actually the longest line, at a length of 46 miles.

Section

1: West Ruislip to Marble Arch via West Acton

Logistically,

after tying up the various western arms of the District Line in the one trip,

this was a bit of a doddle. The idea was to start at West Ruislip, work my way

via the train to Hanger Lane, then take a walk to West Acton Station, which

would mean I could then get straight onto an eastbound train, having already

sketched Ealing Broadway for the District Line. Time permitting, this would

offer me the option of walking between Queensway and Marble Arch if I was

feeling particularly energetic – or if tube fatigue was badly setting in at

this point. I’d already sketched 5 stations which were also on either

Piccadilly or District lines, so this left me 44. Doing a marathon stint

working eastwards from the west, I reckoned that I could bag 16 of them on this

first trip and leave only 28 to be done in a further 2 trips.

The stations

on the two western arms of the Central Line suffer from having been largely

designed in the 30s, for the Central Line Extension which was part of the New

Works programme. That in itself isn’t the problem. However, the building of the

line and the stations thereon was interrupted by the Second World War, so what

we had was stations originally designed in the 1930s, eventually being

completed in the 1930s, with their designs modified by a different architect,

during the period of post war austerity. So, whereas on the Uxbridge arm of the

Piccadilly Line many of the stations completed before the war bear the distinct

hallmarks of the work of Charles Holden, the stations between West Ruislip and

Hanger Lane seem to most of them be by completely different hands, despite some

of them having at least originated from the drawing board of Brian Lewis.

Brian Lewis was an Australian architect

who moved to Britain in 1928.He worked extensively for the Great Western

Railway until the war, then again until 1947 when he returned to Australia to

lecture on architecture at Melbourne University.

According to

my research (which may well be in error), the terminus, West Ruislip, was designed by John Kennett and Roy Turner, though.

I wouldn’t say that it’s as pleasing to the eye as one of Charles Holden’s

finest, but it has its appealing features, which is all the better considering

the age of austerity in which it was built. I like the glazed ticket hall

rising above the canopy. That in itself is worthy of mention too. Typically the

canopies of stations built in the 30s, or stuck later onto earlier stations are

thick, blocky and horizontal. This canopy tapers gently upwards and away from

the station buildings, which is rather appealing as well.

According to

my research (which may well be in error), the terminus, West Ruislip, was designed by John Kennett and Roy Turner, though.

I wouldn’t say that it’s as pleasing to the eye as one of Charles Holden’s

finest, but it has its appealing features, which is all the better considering

the age of austerity in which it was built. I like the glazed ticket hall

rising above the canopy. That in itself is worthy of mention too. Typically the

canopies of stations built in the 30s, or stuck later onto earlier stations are

thick, blocky and horizontal. This canopy tapers gently upwards and away from

the station buildings, which is rather appealing as well.

Pastures new, in this case, were

represented by our first Brian Lewis/ FCC Curtis station, South Ruislip. South Ruislip’s entrance hall is topped by a

striking rotunda, as are those at Chiswick Park and Arnos Grove. However both

of these have brick rotundas with glazed panels. South Ruislip’s rotunda is

constructed from some translucent light blue panels which unfortunately give it

something of the appearance of a gasometer- well, to those of us of a certain

age who remember gasometers anyway. Maybe that’s a bit of an unfair comparison

since this is a pretty striking piece of work by anyone’s standards, and

certainly a relief after the disappointment of Ruislip Gardens.

My grandmother’s sister, Auntie Eileen

and her husband Uncle Ted lived in Northolt, in a street called Islip Manor

Road if I recall correctly. I used to love visiting them. They had a bungalow,

with a massive garden to play in, and I remember Uncle Ted as a huge, white

haired, very funny guy. They had no kids of their own, so they always made a

real fuss of us. Every time I can remember visiting them, though, we went by

car, so my mind, as regards Northolt

Station, was something of a blank canvas. What can I say? Well, it’s better

than Ruislip Gardens. The windows of the raised ticket hall for my money don’t

work quite as well as the panels at West Ruislip, and I think that the

appearance of the station would be improved with a canopy like that at West

Ruislip, instead of the short stubby one there now.

There was neither the desire nor the

time to linger outside Northolt, since I was eager to knock off the next

station, Greenford, and then get to Perivale to begin the walked section

of this trip. But actually Greenford was well worth stopping for. You wouldn’t

necessarily say that it’s hard to believe that Greenford could have been

designed by the same architects as Northolt, but at least for the first time on

this trip I’ve seen a station that clearly belongs to the same network as

Holden’s work on the Piccadilly. With its raised booking hall, similar to those

at Northolt and West Ruislip, its rounded brown brickwork and tower, and the sinuous

curve of the original canopy, it’s a real cut above Northolt, and yet it’s

another Brian Lewis design which was finished by FCC Curtis. You won’t have to

do a great deal of in depth research to find out that Greenford was one of a

few stations where the escalators went straight up to and emerged on the

platforms themselves, and that it was the last station with a wooden escalator,

since they were all replaced following the 1987 King’s Cross fire. It took them

27 years to get round to Greenford, mind you. It’s been replaced by an

inclinator, which is like the kind you see in very large supermarkets, and

rightly so, considering the network’s commitment to improving disabled access

at its stations, which could still rightfully be described as poor.

This trend for aesthetically improving

stations continues as I alight to start my walk at Perivale. I find its curved brick façade, with original canopy and

tall glazed panels above the canopy to be very appealing. Once again, I feel

that it can happily rub shoulders with Holden’s work amongst the ranks of the

best looking stations of the network. Like Greenford, Perivale was designed

before the war by Brian Lewis, but not completed until after the war by FCC

Curtis. If I were to make a criticism, or rather an observation, the station

does just look the tiniest bit unbalanced due to the lack of a wing on the

right which would mirror the one on the left. This slightly spoils the

symmetry, and a little research revealed that there was originally supposed to

be a wing there, and also a tower, but they were never built. Due to post war

austerity, I shouldn’t wonder. Still, instead of mourning what wasn’t there, I

was very pleased to praise what was there.

I hiked along the

unlovely A40, as far as the even unlovelier Hanger Lane gyratory system, that

perennial fixture in radio traffic reports, most of the time accompanied by the

words, ‘traffic jam’, ‘huge tailback’ and ‘avoid like the plague’. Yet in the

middle of the notorious traffic interchange sits the rather beautiful and

gemlike Hanger Lane station. This

didn’t come as a surprise to me, bearing in mind the number of times I’ve

driven around it. Still, the scene is a very graphic visual representation of

the advantages of taking the tube over driving in London. In some ways it is

reminiscent of Holden’s Arnos Grove and Southgate stations, although the ground

level of the station is not a complete circle like the glazed booking hall is.

In a way, Hanger Lane station completes the journey through the Brian Lewis/ FCC

Curtis stations, from the mundane Northolt, to the rather stylish Greenford,

the impressive Perivale, and now this little gem here. It’s certainly my favourite Central Line

station so far, and I think that it could well find itself in my list of

favourite stations on all lines by the time I complete the challenge. It’s

difficult to divorce the station from its context, which for me makes it even

more special, a diamond in the rough, if you like.

To reach my

next station, West Acton, by tube, I’d have to go on to North Acton, and then

get a train heading towards Ealing Broadway, and then come back through North

Acton to the next station east, East Acton. Well, that’s the kind of messiness

I want to avoid if I can, so I continue my walk to West Acton station. To be honest, it doesn’t exactly allow West

London to its best effect, the walk from Hanger Lane to West Acton Station,

but still, best foot forward and all that. As for West Acton station, well,

it’s the most Holdenesque station I think I’ve yet encountered on the Central

Line. Once again it’s Brian Lewis, but this is a pure Brian Lewis station,

since it was opened in 1940. The street level entrance is a low, wide, brown

brick structure, similar to Holden’s work, and like this, it is topped by a

large rectangular ticket hall. This structure, though, is something quite

different from a typical Holden arrangement. Only the two sides of the hall are

built from brick with the front being thin glass vertical panels in what looks

like Portland stone. I like it – maybe not more than I like Hanger Lane, but it

has appeal. It’s the sort of building which, if you removed the tube roundels,

and the blue strips with the station’s name, and showed me a photograph, I’d

still say – that looks like a London tube station.

So, getting back on the train at West

Acton, from here until the end of this trip at Marble Arch it’s relentlessly

eastwards along the line, running the gamut of the Actons. South Acton used to

be on the District Line, but that stopped before I was born, although it’s now

on the Overground. The next Acton I stop at, though, is North Acton, and what a surprise this little station is. It’s the

first station I’ve encountered along this western stretch of the line which was

actually opened before the start of world war 2, and it’s perfectly compact,

comfortable and cosy, almost cottage like with the sloping porch and the

hanging baskets by the doorway. The platform itself looks even more like a

small countryside station, which I rather like too.

East Acton is the nearest station to

Hammersmith Hospital, and also to HMP Wormwood Scrubs Prison. I used the

station when I was an inmate of one of these two establishments. I will leave

it to your imagination which. Strictly speaking, this isn’t Acton at all. Acton

is in my home borough, Ealing, and this is over the border in our neighbours

Hammersmith and Fulham. This one is just as cosy and quaint as North Acton, but

even a couple of years older, first opening in 1920. In appearance it’s not a

million miles removed from Wimbledon Park on the District, what with that

sharply pitched roof, although it doesn’t come to a pyramidal point. I have to

say that I was pleasantly surprised by this stretch of the Central Line. I

mentioned how I used to go skating in Richmond when I was 11 or 12. Well, when

I got a year or two older, I discovered the rather more exclusive rink at

Queensway, and used to travel there from Ealing Broadway using the Central

line. From the train window it had never struck me that any of the stations

overground were really that much to write home about.

I have several

memories of White City. It always

seemed to be the station where the trains were held for a ridiculous amount of

time before being allowed to leave. After completing my A levels but before starting

at uni, I worked for a temp agency in Ealing Broadway, and they would send you

to several places owned by the BBC throughout West London to wash up in their

canteens. When I worked in TVC (Television Centre in Wood Lane to you) then I’d

take the tube to White City. TVC is still there right opposite the entrance to

the tube, although the BBC are long gone now. Then, over a decade ago, during

my quizzing days I made appearances in a number of TV quiz shows in TVC, which

again necessitated a visit to White City. Incidentally, I’m sure you already

know that the name White City was inspired by the Franco British Exhibition and

the Olympic Games of 1908. The buildings erected, including the Stadium

(demolished in the mid 80s) were a brilliant white, hence the nickname which

stuck. I found a plaque on the outside which commemorated a different

exhibition, the 1951 Festival of Britain, where the station, only opened a few

years, won a design award. You pays yer money . . .

Onwards underground from here, then. As

for the next station, Shepherd’s Bush,

well, things sure have changed here on Walton’s Mountain. Last time I was in

these particular parts, the Central Line Shepherds Bush station was a fairly

humble, Edwardian looking single story edifice. Nothing to get too excited

about, but certainly nothing to feel offended about either. Since then, though,

somebody knocked it down, and put a much, much bigger modern glass station in

its place. Well, look, my default reaction to old buildings being replaced by new

ones is regret, but let’s be fair, you can’t keep everything just because it’s

old. The old Shepherd’s Bush was perfectly nice, but not an outstanding example

of the genre as it was. The new station

is sleek, shiny and modern. Whether we’ll still feel that way in 100 year’s

time is anyone’s guess. I’ll be long gone, anyway.

If it had

ever come to a choice between keeping the old Shepherd’s Bush station, or Holland Park station, then I’m glad

that they chose the latter. The building was refurbished in the 1990s, but I’m

guessing that it looks largely as it did when it opened in 1900. It was

designed by one Harry Bell Measures. Harry Bell Measures was a successful

architect in the last years of the 19th century and the early

decades of the 20th, and he was the chief architect for the original

stations on the Central London Railway. Only this station, Queensway, and the

Central line exit of Oxford Circus remain to show us his work on the line – a

couple of other entrances remain, but are apparently totally unrecognisable as

his original work. I have to say that’s a bit of a shame.

Well, if you remember, we’ve already

done Notting Hill Gate when we followed the Edgware Road arm of the District,

so I stay on the train all the way to Queensway.

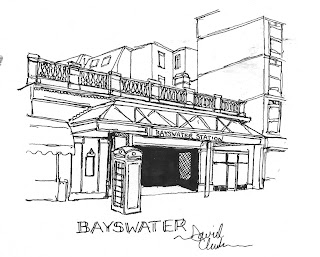

Now, all the time I was visiting the ice rink, the station at Queensway struck

me as little more than a lift up to the street level. So I was quite surprised

to emerge and see a rather nice Harry Bell Measures station. To be fair they’ve

added a rather elegant metal and glass semi circular canopy since last I came

this way. I suppose that I never really noticed the station building because of

the ruddy great hotel built on top of it. I did have half a mind to sketch

Queensway at the same time as I visited Bayswater on the District, which can’t

be much more than 100 yards down the road. On reflection I’m glad that I didn’t

then, since I’m not seeing it as part of a continuum.

The

penultimate station of the day is Lancaster

Gate. Research tells me that the redesigned, rather nondescript façade was

opened in the noughties, yet as I emerge from it I am instantly struck by a

feeling of déjà vu. I have been through this redesigned entrance before . . .

only I’m not sure when. Possibly it might have been the only time I stayed in

London overnight when I was participating in a glitzy quiz charity event in

about 2010, but when you get right down to it, I just don’t remember when. Mind

you, I’m surprised with myself that I remember this entrance at all. The grey

metal cladding just looks depressing, and the stainless steel doorways lack

inspiration. To be honest, it looks just like a suburban shopping mall.

Chin up though,

we’re nearly at the end of today’s trip. I did think that Marble Arch was completely underground and accessed only by

stairways and subways, which is the only way that I’ve ever entered or exited

the station. Yet I found this rather unassuming entrance. I’ve not seen a

structure like the red and black one with the roundels above the station name

on my travels

before. It’s quite nice actually. Running out of things to say about the station itself, I pause to think about the eponymous arch, and wonder how many people passing it know that it used to stand on the Mall as the gateway to Buckingham Palace. If it commemorates anything nowadays, it’s the site of the infamous Tyburn, a place where the guilty – and sometimes even the not so guilty – were hanged for the edification of the good people of London. Makes you proud, doesn’t it.

before. It’s quite nice actually. Running out of things to say about the station itself, I pause to think about the eponymous arch, and wonder how many people passing it know that it used to stand on the Mall as the gateway to Buckingham Palace. If it commemorates anything nowadays, it’s the site of the infamous Tyburn, a place where the guilty – and sometimes even the not so guilty – were hanged for the edification of the good people of London. Makes you proud, doesn’t it.

------------------------------------------------

This first

section of the Central seemed relatively easy to me. Maybe I was just in the

right mood for such a trip. Whatever the case, I was filled with a sense of

achievement on the realisation that, with the exception of the Metropolitan Line

arm to Amersham, Chesham and Watford, and also South Harrow, I’d pretty much

done the stations in West London.